Why A

April 2, 2006 9:11 AM Subscribe

Why do the letters of the alphabet occur in the particular order that they do?

Nothing I could find in a trawl of Wikipedia articles on the Latin Alphabet, the Greek Alphabet or the History of the Alphabet seemed to have the answer. There is a lot of discussion on history and on particular letters - but nothing that seems to explain to me how we came up with a sing-song sequence somewhere between the Pheonicians and Sesame Street.

Nothing I could find in a trawl of Wikipedia articles on the Latin Alphabet, the Greek Alphabet or the History of the Alphabet seemed to have the answer. There is a lot of discussion on history and on particular letters - but nothing that seems to explain to me how we came up with a sing-song sequence somewhere between the Pheonicians and Sesame Street.

Best answer: I have always wondered this. I called the Seattle Public Library's answer line about this maybe ten years ago. They took my information, said they would "research it" and get back to me. They got back to me a few days later and said "we don't know." Ask Yahoo doesn't know either, though it links to this article which is good reading.

posted by jessamyn at 9:28 AM on April 2, 2006

posted by jessamyn at 9:28 AM on April 2, 2006

Well, I don't have an answer, but here's a sub-question that might give us some hints: Are there other languages that use the Latin alphabet that traditionally (or currently) had (have) the letters in another order? If we can identify when those languages split off from the branch that led to English, we can at least figure out when the order was laid down, and maybe that will help determine why.

posted by Rock Steady at 9:33 AM on April 2, 2006

posted by Rock Steady at 9:33 AM on April 2, 2006

Best answer: rock steady, that "history of the alphabet" link above explains that essentially every alphabet derives from a "proto-canaanite" alphabet which was also the numerical system. If you used letters to represent numbers, then they would need to be in order - hence an order was devised, but only based on which letters stood for which numbers, which just comes down to a choice of naming, and the fact that every language on earth uses different sounds to mean things is evidence that there is some just plain randomness to nomination (yes, there is some onomatopeia, etc, but that is a) exception, not rule, and b) not universal anyway)

posted by mdn at 9:42 AM on April 2, 2006

posted by mdn at 9:42 AM on April 2, 2006

The answer is easy. They have to be in alphabetic order.

posted by megatherium at 10:12 AM on April 2, 2006

posted by megatherium at 10:12 AM on April 2, 2006

Suppose, just for a moment, that the order had been a different one. Wouldn't you still be able to ask that question?

It's got to be some order, after all.

posted by Steven C. Den Beste at 10:13 AM on April 2, 2006

It's got to be some order, after all.

posted by Steven C. Den Beste at 10:13 AM on April 2, 2006

I think "it had to be in some order" is a bit of a silly answer. It'd be perfectly plausible for the letters to just be used to make words, and not be written in an order at all. What "order" is punctuation in, for example?

posted by reklaw at 10:21 AM on April 2, 2006

posted by reklaw at 10:21 AM on April 2, 2006

Best answer: There is a lot of discussion on history and on particular letters - but nothing that seems to explain to me how we came up with a sing-song sequence somewhere between the Pheonicians and Sesame Street.

I don't know where the sequence comes from, but the melody of the song comes from an old French country song, and wasn't set to the alphabet untill 1834.

posted by maxreax at 10:37 AM on April 2, 2006

I don't know where the sequence comes from, but the melody of the song comes from an old French country song, and wasn't set to the alphabet untill 1834.

posted by maxreax at 10:37 AM on April 2, 2006

According to the ISO

! " # $ % & ' ( ) * + , - . / : ; <> ? @ [ \ ] ^ _` { | } ~

Is the order of punctuation.

posted by public at 11:01 AM on April 2, 2006

! " # $ % & ' ( ) * + , - . / : ; <> ? @ [ \ ] ^ _` { | } ~

Is the order of punctuation.

posted by public at 11:01 AM on April 2, 2006

These guys make a claim, but I'm not sure if I believe them.

posted by StickyCarpet at 11:02 AM on April 2, 2006

posted by StickyCarpet at 11:02 AM on April 2, 2006

I'm pretty sure mdn's got it: hebre/aramaic letters also represent numbers -and have done so for at least 2.5k+ years - and they were written in this numerical order.

WHY that order was chosen, well, ask the kabbalists. but prepare for a long, long answer involving gibberish

posted by lalochezia at 11:28 AM on April 2, 2006

WHY that order was chosen, well, ask the kabbalists. but prepare for a long, long answer involving gibberish

posted by lalochezia at 11:28 AM on April 2, 2006

Best answer: This exact question is answered in the book "Imponderables: The Solution to the Mysteries of Everyday Life" by David Feldman. It's a rather long, messy answer, spanning 5 different cultures. I'm not going to type the whole thing out(sorry), but I will try to give a summary.

THE EGYPTIANS

The Egyptians had 5 distinct stages of writing, with the last stage being very close to the alphabet as it is today. However, even with the advent of letter sounds, they still clung to the first 3 stages.

1. Hieroglyphs as pictures of things: "horse" is a picture of a horse. Every single word needs it's own character, and abstract concenpts cannot be represented.

2. Idea Pictures: a leg can mean not only leg, but running or fast

3. Sound Pictures: One symbol was now used to describe a sound that existed in words of a spoken language rather than a graphic description of the word signified.

4. Syllable Pictures: The same syllable hieroglyph can now appear in many different words.

5. Letter sounds: One symbol now took the place of one letter in a word. They eventually whitted the redundant letters down to 25.

THE UGARITS

Although the Phoenicians are widely hailed as the inventors of the alphabet, it's now that that it originated in the city of Ugarit in northwest Syria. A tablet was found that has Ugaritic letters displayed opposite a column of known Babylonian syllabic signs, proving that the Ugarits conciously order their alphabets. Although the phonetics of the Ugaritic alphabet were identical to that of the Phoenicians, the actual script was different from the later Phoenician alphabet and the earlier Egyptian and Semetic languages.

THE PHOENICIANS

Although the Phoenician alphabet probably developed about the same time as the Ugarits, they are much more important because they spread their alphabet throughout much of the world. They were traders who used their alphabet to track inventories, standardize accounting procedures, etc; they left no literature or books behind. They carried their alphabet to most of the major Mediterranian ports by 1000 BC.

They had totally dropped out picture sounds and kept only the symbols that signified sounds. The Phoenician's work "aleph" meant "ox," and the letter "a" was made to look like a ox's head. The ox, the most important animal of the time, was the basis for the first letter of most European and Semetic languages, including later, English. They also had no vowels.

THE GREEKS

The Greeks took their favorite elements from the Semetic and Phoenician languges. They took 16 consonants from the Phoenician language and addes five vowels: alpha, epsilon, upsilon, iota, omikron. Alpha became the first letter of the Greek alphabet. They was not taken from the Phoenician aleph, which was a consonant, but from the Hebrew language, where aleph also happened to mean ox. The first letters of the Hebrew alphabet are "aleph, beth, gemel, dalth," which mean "ox, house, camel, door." The Greek equivilants are alpha, beta, gamma, delta. The Greeks needed vowels to express the sounds they made in their language. The Phoenicians did not have them, and though the Hebrew language did inclufe some vowel sounds,, they were used erratically and sporadically. So the Greeks took Hebrew consonants that had no use in speaking Greek(like aleph) and converted them into vowels.

By adding a few consonants of their own, they ended up with 24 letter alphabet. They had no c or v, and some of their letters stood for different sounds than they do now. However, the order was pretty much the same as it is today, with a few exceptions(z was 6th letters).

THE ROMANS

The Romans were ruled by the Greek speaking Etruscans. Before their declin,e the Romans adopted the Greek alphabet and made changes. They established the current alphabetical order used by English-speaking countries, but with only 23 letters. J, U, and W were added after well after the birth of Christ. There are various reasons why individual letters got changed. Z was originally dropped, not needing a place in Roman speech. When the Romans cionquered Greece, they needed Z back to transliterate Greek wrods into Roman. They had formalized the order by then, though, so Z was dumped at the end.

If I don't get marked as best answer, I am probably going to cry. I am a slow typer.

posted by Juliet Banana at 11:50 AM on April 2, 2006 [4 favorites]

THE EGYPTIANS

The Egyptians had 5 distinct stages of writing, with the last stage being very close to the alphabet as it is today. However, even with the advent of letter sounds, they still clung to the first 3 stages.

1. Hieroglyphs as pictures of things: "horse" is a picture of a horse. Every single word needs it's own character, and abstract concenpts cannot be represented.

2. Idea Pictures: a leg can mean not only leg, but running or fast

3. Sound Pictures: One symbol was now used to describe a sound that existed in words of a spoken language rather than a graphic description of the word signified.

4. Syllable Pictures: The same syllable hieroglyph can now appear in many different words.

5. Letter sounds: One symbol now took the place of one letter in a word. They eventually whitted the redundant letters down to 25.

THE UGARITS

Although the Phoenicians are widely hailed as the inventors of the alphabet, it's now that that it originated in the city of Ugarit in northwest Syria. A tablet was found that has Ugaritic letters displayed opposite a column of known Babylonian syllabic signs, proving that the Ugarits conciously order their alphabets. Although the phonetics of the Ugaritic alphabet were identical to that of the Phoenicians, the actual script was different from the later Phoenician alphabet and the earlier Egyptian and Semetic languages.

THE PHOENICIANS

Although the Phoenician alphabet probably developed about the same time as the Ugarits, they are much more important because they spread their alphabet throughout much of the world. They were traders who used their alphabet to track inventories, standardize accounting procedures, etc; they left no literature or books behind. They carried their alphabet to most of the major Mediterranian ports by 1000 BC.

They had totally dropped out picture sounds and kept only the symbols that signified sounds. The Phoenician's work "aleph" meant "ox," and the letter "a" was made to look like a ox's head. The ox, the most important animal of the time, was the basis for the first letter of most European and Semetic languages, including later, English. They also had no vowels.

THE GREEKS

The Greeks took their favorite elements from the Semetic and Phoenician languges. They took 16 consonants from the Phoenician language and addes five vowels: alpha, epsilon, upsilon, iota, omikron. Alpha became the first letter of the Greek alphabet. They was not taken from the Phoenician aleph, which was a consonant, but from the Hebrew language, where aleph also happened to mean ox. The first letters of the Hebrew alphabet are "aleph, beth, gemel, dalth," which mean "ox, house, camel, door." The Greek equivilants are alpha, beta, gamma, delta. The Greeks needed vowels to express the sounds they made in their language. The Phoenicians did not have them, and though the Hebrew language did inclufe some vowel sounds,, they were used erratically and sporadically. So the Greeks took Hebrew consonants that had no use in speaking Greek(like aleph) and converted them into vowels.

By adding a few consonants of their own, they ended up with 24 letter alphabet. They had no c or v, and some of their letters stood for different sounds than they do now. However, the order was pretty much the same as it is today, with a few exceptions(z was 6th letters).

THE ROMANS

The Romans were ruled by the Greek speaking Etruscans. Before their declin,e the Romans adopted the Greek alphabet and made changes. They established the current alphabetical order used by English-speaking countries, but with only 23 letters. J, U, and W were added after well after the birth of Christ. There are various reasons why individual letters got changed. Z was originally dropped, not needing a place in Roman speech. When the Romans cionquered Greece, they needed Z back to transliterate Greek wrods into Roman. They had formalized the order by then, though, so Z was dumped at the end.

If I don't get marked as best answer, I am probably going to cry. I am a slow typer.

posted by Juliet Banana at 11:50 AM on April 2, 2006 [4 favorites]

Best answer:

FromEvolution of Alphabets

posted by PurplePorpoise at 12:06 PM on April 2, 2006 [6 favorites]

From

posted by PurplePorpoise at 12:06 PM on April 2, 2006 [6 favorites]

mm, that's supposed to be an animated gif. If it isn't animating, try a hard refresh (ctrl+F5) or open this thread again

posted by PurplePorpoise at 12:08 PM on April 2, 2006

posted by PurplePorpoise at 12:08 PM on April 2, 2006

gah! sorry, from The Evolution of Alphabets - the University of Maryland

posted by PurplePorpoise at 12:09 PM on April 2, 2006

posted by PurplePorpoise at 12:09 PM on April 2, 2006

They aren't in an order in all languages. In some languages they're customarily represented in two-dimensional charts, e.g. Japanese hiragana and katakana. But even there, the two axes are in a customary order, e.g. Japanese vowels on the left side of the chart are always in the order a-i-u-e-o.

"Alphebetical order" listings of Japanese words always derive from the order in which hiragana letters appear in that chart.

Any time you linearize anything, there has to be some ordering principle involved.

posted by Steven C. Den Beste at 12:32 PM on April 2, 2006

"Alphebetical order" listings of Japanese words always derive from the order in which hiragana letters appear in that chart.

Any time you linearize anything, there has to be some ordering principle involved.

posted by Steven C. Den Beste at 12:32 PM on April 2, 2006

Why were so many of the letter shapes reversed in the Latin alphabet? Is that also the point at which people started writting/reading from left to right instead of right to left?

posted by willnot at 12:45 PM on April 2, 2006

posted by willnot at 12:45 PM on April 2, 2006

Because, if the letters were in a different order, it simply couldn't be called the alphabet. It might be called the Kappagamm, or the Thetazet, or the Iotamu, etc.

Hey, can you put those files in Iotamuical order, please?

posted by found missing at 12:46 PM on April 2, 2006

Hey, can you put those files in Iotamuical order, please?

posted by found missing at 12:46 PM on April 2, 2006

Purpleporpoise, that is so friggin' cool. This question and the answers are so friggin' cool. You people is so smart!

posted by generic230 at 1:02 PM on April 2, 2006

posted by generic230 at 1:02 PM on April 2, 2006

Best answer: I did a bit of a search, most of what I could find was either kabbalahish or lunar, and didn't seem very authoritative. An introduction in to the Hebrew Alphabet may be useful nonetheless.

The best I could come up with was this passage from 'The Articulatory Basis of the Alphabet' To find the passage, search in the page for "order of the alphabet". I'm not entirely certain what the conclusion is, but it appears to they are saying the order is not "significant".

"There has been equally various speculation about the factors determining the order of the alphabet and argument about whether or not the order has any special significance. Driver has a useful discussion of this: "The order of the Phoenician alphabet is attested by the evidence of the Hebrew scriptures [acrostic Psalms] and confirmed by external authority.. [the step at Lachish]... The most fantastic reasons for the order of the letters have been suggested based, for example, on astral or lunar theories, even to the extent of using South-Semitic meanings of cognate words to explain the North-Semitic names. Another method has been to seek for mnemonic words which the successive letters when combined into words may spell out [ab gad father grandfather -from different language dialects]" (Driver, 1954: 181) "The order of the alphabet has recently been explained as representing a didactic poem.... The latest suggestion is that the order of the letters of the Semitic alphabet is based on the notation of the Sumerian musical scales". (Driver, 1954: 268) Diringer briefly remarks: "As to the order of the letters, various theories have been propounded, but here again [as for the names of the letters] it is highly probable that the matter has no particular significance...There is some appearance of phonetic grouping in the order of the letters of the North Semitic alphabet, but this may be accidental"(Diringer 1968: 169-170)." (emphasis added)

My guess is that the order of the alphabet has evolved in many different directions for many different reasons, as alphabets/languages cross-pollinate and different cultures ascribe different meanings to their alphabets, over time. So I would say the order is not random, but at the same time not explicitly meaningful, rather it is the result of several millennia of evolution and compounded meanings/usuage.

posted by MetaMonkey at 2:07 PM on April 2, 2006

The best I could come up with was this passage from 'The Articulatory Basis of the Alphabet' To find the passage, search in the page for "order of the alphabet". I'm not entirely certain what the conclusion is, but it appears to they are saying the order is not "significant".

"There has been equally various speculation about the factors determining the order of the alphabet and argument about whether or not the order has any special significance. Driver has a useful discussion of this: "The order of the Phoenician alphabet is attested by the evidence of the Hebrew scriptures [acrostic Psalms] and confirmed by external authority.. [the step at Lachish]... The most fantastic reasons for the order of the letters have been suggested based, for example, on astral or lunar theories, even to the extent of using South-Semitic meanings of cognate words to explain the North-Semitic names. Another method has been to seek for mnemonic words which the successive letters when combined into words may spell out [ab gad father grandfather -from different language dialects]" (Driver, 1954: 181) "The order of the alphabet has recently been explained as representing a didactic poem.... The latest suggestion is that the order of the letters of the Semitic alphabet is based on the notation of the Sumerian musical scales". (Driver, 1954: 268) Diringer briefly remarks: "As to the order of the letters, various theories have been propounded, but here again [as for the names of the letters] it is highly probable that the matter has no particular significance...There is some appearance of phonetic grouping in the order of the letters of the North Semitic alphabet, but this may be accidental"(Diringer 1968: 169-170)." (emphasis added)

My guess is that the order of the alphabet has evolved in many different directions for many different reasons, as alphabets/languages cross-pollinate and different cultures ascribe different meanings to their alphabets, over time. So I would say the order is not random, but at the same time not explicitly meaningful, rather it is the result of several millennia of evolution and compounded meanings/usuage.

posted by MetaMonkey at 2:07 PM on April 2, 2006

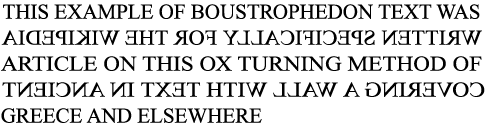

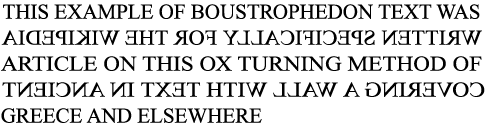

#willnot: Why were so many of the letter shapes reversed in the Latin alphabet? Is that also the point at which people started writting/reading from left to right instead of right to left?

Also around that time there was also Boustrophedon writing (as the ox plows).

posted by MonkeySaltedNuts at 5:52 PM on April 2, 2006

Also around that time there was also Boustrophedon writing (as the ox plows).

posted by MonkeySaltedNuts at 5:52 PM on April 2, 2006

Best answer: I got interested in this now. Some more links for fun:

An interesting 'family tree' of the alphabet from the very cool ancientscripts.com.

The Alphabet Effect: A Media Ecology Understanding of the Making of Western Civilization (google cache, pdf here)

This seems interesting, though I just scanned it, there is an awful lot of information on the orgin and evolution of the alphabet. Select quotes:

"Our hypothesis is that the emergence of writing and mathematics represents an evolution of spoken language which can be modeled in terms of Prigogenian bifurcations in which new levels of order emerge from the chaos of the information loads that developed when speech could no longer handle the complexity of large scale agricultural activity in the city-states of Sumer circa 3,100 B.C." (p20)

"The alphabetic order of the letters became fixed for the first time with the Ugaritic script of the fourteenth to thirteenth century. With rare exception all alphabetic scripts follow the same order, indicating their common origin." (p29)

The argument seems to be that the origin of the alphabet is in accounting and record-keeping for agriculture and trade. That is, the alphabet as we know it derives from early efforts to work with numbers. Which suggests that the order of the letters are, by reverse engineering, the letters/concepts that match the numbers they represent. I'm not sure if that makes sense. Try reading the straight dope staff report on numerology to get the gist.

I shall attempt to explain slightly better. The order of the alphabet started out as a way to represent the numbers 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9, 10,20,30,40,50,60,70,80,90 (and a few hundreds here and there), which also may have been associated with concepts (such as A=Ox, B=House).

At this point a letter can be simultaneously a number, a concept and a letter as we know it. Various cultures/peoples may have ascribed their own meanings to certain letters over this period, most notably (for the English alphabet) the Semitic and Greek alphabets.

Over time, presumably as numbers are developed and mathematics is worked out, the value of letters as numbers decreases, and the value of letters as communicators of words increases. However, as is seen in the bible, words may be constructed with numerical values in mind, and letter's numerical correspondance is important in the alphabets of many different cultures.

From this point on the alphabet speads, mutating according to local preferece and speech patterns, with no discernable importance attached to order, except to preserve it when appropriate and to group common sounds. Eventually it becomes standardised and more or less hardens in to the patterns we find it in today.

In short, there is meaning in the order, but the meaning of many different peoples over a very long time. Note this is all just my speculation based on a little reading, but it sounds reasonable to me.

posted by MetaMonkey at 10:44 PM on April 2, 2006

An interesting 'family tree' of the alphabet from the very cool ancientscripts.com.

The Alphabet Effect: A Media Ecology Understanding of the Making of Western Civilization (google cache, pdf here)

This seems interesting, though I just scanned it, there is an awful lot of information on the orgin and evolution of the alphabet. Select quotes:

"Our hypothesis is that the emergence of writing and mathematics represents an evolution of spoken language which can be modeled in terms of Prigogenian bifurcations in which new levels of order emerge from the chaos of the information loads that developed when speech could no longer handle the complexity of large scale agricultural activity in the city-states of Sumer circa 3,100 B.C." (p20)

"The alphabetic order of the letters became fixed for the first time with the Ugaritic script of the fourteenth to thirteenth century. With rare exception all alphabetic scripts follow the same order, indicating their common origin." (p29)

The argument seems to be that the origin of the alphabet is in accounting and record-keeping for agriculture and trade. That is, the alphabet as we know it derives from early efforts to work with numbers. Which suggests that the order of the letters are, by reverse engineering, the letters/concepts that match the numbers they represent. I'm not sure if that makes sense. Try reading the straight dope staff report on numerology to get the gist.

I shall attempt to explain slightly better. The order of the alphabet started out as a way to represent the numbers 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9, 10,20,30,40,50,60,70,80,90 (and a few hundreds here and there), which also may have been associated with concepts (such as A=Ox, B=House).

At this point a letter can be simultaneously a number, a concept and a letter as we know it. Various cultures/peoples may have ascribed their own meanings to certain letters over this period, most notably (for the English alphabet) the Semitic and Greek alphabets.

Over time, presumably as numbers are developed and mathematics is worked out, the value of letters as numbers decreases, and the value of letters as communicators of words increases. However, as is seen in the bible, words may be constructed with numerical values in mind, and letter's numerical correspondance is important in the alphabets of many different cultures.

From this point on the alphabet speads, mutating according to local preferece and speech patterns, with no discernable importance attached to order, except to preserve it when appropriate and to group common sounds. Eventually it becomes standardised and more or less hardens in to the patterns we find it in today.

In short, there is meaning in the order, but the meaning of many different peoples over a very long time. Note this is all just my speculation based on a little reading, but it sounds reasonable to me.

posted by MetaMonkey at 10:44 PM on April 2, 2006

I came in to say it was because the ox was the most important animal of its day, but I see that Juliet Banana has saved me a lot of trouble. (I read the same book.) Thanks, Juliet!

posted by LeLiLo at 1:30 AM on April 3, 2006

posted by LeLiLo at 1:30 AM on April 3, 2006

And I just came in to share that when I read this question, there were 26 responses ;)

posted by UnclePlayground at 10:32 AM on April 3, 2006

posted by UnclePlayground at 10:32 AM on April 3, 2006

Steven C. Den Beste, the Japanese Hiragana and Katakana do have a special order that does make sense: it is the same order that you see in the charts. Technically, Hiragana and Katakana are not alphabets, they're syllabaries. What you are looking at when you see all those squiggles are not letters, they're sounds. That hit me one day when I asked a Japanese man how to spell his name and he said: tsu-ru-ka-wa. Each symbol stands for something we think of in letters, but it's really just its own noise.

The order that you find in a syllabary is generally dictated by where in the mouth the sound is made. This is true in the Japanese system and in Sanskrit Devanagari as well:

They start with the Vowels: these can be made with the mouth open and at the back of the throat: aaa, oooo.

Then Velars, sounds you make by constricting your throat to manipulate the vowels: ka, ga, and some funky na's.

Next is Palatals, the back of the tongue on the palate: ja.

Some languages have retroflex Cerebrals, a curling back of the tongue, which in the Indian languages gives us that Apu sound: some kinds of ta's and da's.

In English, we use mainly Dentals instead (though we have a lot of hybrids between the two): sounds formed on the teeth with the tongue: ta, da, na.

Labials come next with trapped air being released at the lips: pa, ba, ma.

The last things are usually Sibilants (s's and sh's), Aspirates (ha) and Semivowels (ya, ra, wa) which are all created by pushing air out through different lip shapes or (in the case of ya) throat movement. Sanskrit and Japanese both end on n/m, a sort of mutable symbol which means just close the mouth and hum.

So if you look back at all these sounds, they start where we make them at the back of the throat and go all the way up, step by step, to past the lips. It makes sense! Unfortunately for this thread, it only makes sense for syllabaries...it can't help us with English!

posted by simonemarie at 8:04 AM on April 5, 2006 [1 favorite]

The order that you find in a syllabary is generally dictated by where in the mouth the sound is made. This is true in the Japanese system and in Sanskrit Devanagari as well:

They start with the Vowels: these can be made with the mouth open and at the back of the throat: aaa, oooo.

Then Velars, sounds you make by constricting your throat to manipulate the vowels: ka, ga, and some funky na's.

Next is Palatals, the back of the tongue on the palate: ja.

Some languages have retroflex Cerebrals, a curling back of the tongue, which in the Indian languages gives us that Apu sound: some kinds of ta's and da's.

In English, we use mainly Dentals instead (though we have a lot of hybrids between the two): sounds formed on the teeth with the tongue: ta, da, na.

Labials come next with trapped air being released at the lips: pa, ba, ma.

The last things are usually Sibilants (s's and sh's), Aspirates (ha) and Semivowels (ya, ra, wa) which are all created by pushing air out through different lip shapes or (in the case of ya) throat movement. Sanskrit and Japanese both end on n/m, a sort of mutable symbol which means just close the mouth and hum.

So if you look back at all these sounds, they start where we make them at the back of the throat and go all the way up, step by step, to past the lips. It makes sense! Unfortunately for this thread, it only makes sense for syllabaries...it can't help us with English!

posted by simonemarie at 8:04 AM on April 5, 2006 [1 favorite]

Response by poster: I am amazed by the depth, breaths and variety of answers people have come up for this. Thank you for your contributions. I had never really given much thought to just what a clever invention the alphabet is for conveying language concisely. In terms of sequence I find it rather unsatistying to think that the original order may have been random when it could have been a counting system or a nmemonic or some other kind of classification. I guess we may never know.

posted by rongorongo at 8:54 AM on April 5, 2006

posted by rongorongo at 8:54 AM on April 5, 2006

Dagnabbit. Now I have the "bang, quote, pound, dollar, percent, ampersand, tick, open close parentheses, asterisk, plus, comma, minus, period, slash, colon, semicolon, less than, greater than, question mark, at-sign, left bracket, backslash, right bracket, caret, underscore, backtick, left curly brace, right curly brace, tilde" song going through my head..

posted by ooga_booga at 10:01 PM on April 5, 2006

posted by ooga_booga at 10:01 PM on April 5, 2006

It might also be noted that not all languages have songs for remembering the order of their alphabet. When I was learning Russian it came as quite a surprise that such a thing doesn't exist. I'd love to see chart for which languages have songs and which do not.

posted by filchyboy at 10:06 PM on April 5, 2006

posted by filchyboy at 10:06 PM on April 5, 2006

A sort-of-self-link, but here's an old McSweeney's list of alternate alphabetical orders I sent in a long time ago. They all seem all wrong.

posted by phmk at 9:01 AM on April 20, 2006

posted by phmk at 9:01 AM on April 20, 2006

This article is somewhat related, arguing that across writing systems letters seem to correspond to features of the natural world. Or maybe it isn't related at all but might be interesting to someone interested in the ordering of the alphabet.

posted by OmieWise at 6:31 AM on April 21, 2006

posted by OmieWise at 6:31 AM on April 21, 2006

Similar questions include "Why does the water in the puddle always fit the hole in the road so well?"

posted by A189Nut at 3:27 PM on April 21, 2006

posted by A189Nut at 3:27 PM on April 21, 2006

Is there any doubt why this question is so difficult to answer? Especially when we don't even have a definitive answer as to why the keyboard (typewriter) is arrainged the way it is. This from a device that came to market in the late 1800's.

If it is arbitrary then perhaps we are in need for a re-ordering using a new system. I suggest that the elements table be used as a guide. We should place the letters by atomic weight. S is the lightest and will be first, K is the heaviest and is last.

Since this is new ground I am open to suggestions for the order of the other 24. But not M. M is exactly right as the middle letter. It is an anchor from which the other letters increase or desend.

Vowels are 'rare letters' and are grouped separately. These letters are actual sounds, as anyone with an infant will tell you. Interestingly the M sound is also easily produced by infants. Is it any wonder than that the word 'mother' has a common sound in many languages?

posted by goodman at 4:24 AM on April 24, 2006

If it is arbitrary then perhaps we are in need for a re-ordering using a new system. I suggest that the elements table be used as a guide. We should place the letters by atomic weight. S is the lightest and will be first, K is the heaviest and is last.

Since this is new ground I am open to suggestions for the order of the other 24. But not M. M is exactly right as the middle letter. It is an anchor from which the other letters increase or desend.

Vowels are 'rare letters' and are grouped separately. These letters are actual sounds, as anyone with an infant will tell you. Interestingly the M sound is also easily produced by infants. Is it any wonder than that the word 'mother' has a common sound in many languages?

posted by goodman at 4:24 AM on April 24, 2006

One can certainly imagine a more appealing order for the alphabet based on the shapes of the letters - there are tantalising hints of such an order already. Just thinking of capitals, E and F are rightly together but should be joined by L and probably I. B, P and R should be together, as should O, Q , C and G. V and W are together, as are M and N, but arguably all four should follow on. You see what I mean.

It's interesting that runes, which are supposed to derive from the mainstream alphabet, don't follow the same order, hence the alternative name futhorc for Anglo-Saxon ones, after the first seven letters - though I'm not sure whether this order is really ancient or invented by relatively modern scholars?

posted by Phanx at 8:09 AM on April 24, 2006

It's interesting that runes, which are supposed to derive from the mainstream alphabet, don't follow the same order, hence the alternative name futhorc for Anglo-Saxon ones, after the first seven letters - though I'm not sure whether this order is really ancient or invented by relatively modern scholars?

posted by Phanx at 8:09 AM on April 24, 2006

Best answer: One can certainly imagine a more appealing order for the alphabet based on the shapes of the letters...

The Arabic alphabet is ordered pretty much on this principle. All the letters of similar shape are grouped together. You can compare and contrast it with, say, the Hebrew alphabet, to see how much it was changed.

Interestingly enough, Arabic letters have also been used as numbers, but usually according to the abjadi ordering, which mirrors the order of letters in the Phoenician, Aramaic, and Hebrew alphabets.

posted by skoosh at 1:18 PM on December 18, 2006

The Arabic alphabet is ordered pretty much on this principle. All the letters of similar shape are grouped together. You can compare and contrast it with, say, the Hebrew alphabet, to see how much it was changed.

Interestingly enough, Arabic letters have also been used as numbers, but usually according to the abjadi ordering, which mirrors the order of letters in the Phoenician, Aramaic, and Hebrew alphabets.

posted by skoosh at 1:18 PM on December 18, 2006

This thread is closed to new comments.

It is also a numerical order, but that is not a cause so much as an effect (& even if it were a cause, the naming of the numbers is random - not everything has an essential nature, ya know.)

posted by mdn at 9:26 AM on April 2, 2006 [1 favorite]